A new children’s book, The Seed Who Was Afraid To Be Planted (Sophia Institute Press, 2019), is getting rave reviews from moms, Catholic media, and conservative celebrities.

On the surface, it’s a simple, inspiring story about courage and change; but for many kids — and for many adults who have suffered abuse — the pictures, text, and message will be terrifying and even dangerous. At best, this children’s book delegitimizes normal emotions. At worst, it could facilitate abuse.

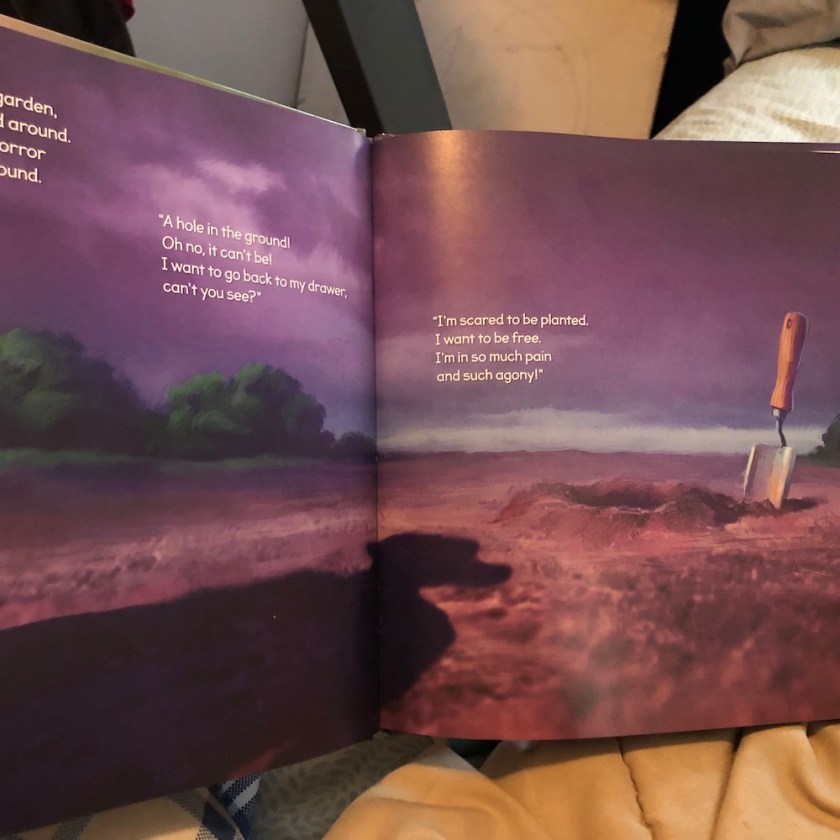

The rhymed verses by Anthony DeStefano, lavishly illustrated by Erwin Madrid, tell the story of a little seed who’s plucked from his familiar drawer

and planted in the earth. He’s frightened and confused, but soon realizes that change means growth, and as he’s transformed into a beautiful, fruitful tree, he becomes thankful to the farmer who planted him, is grateful and happy, and forgets his fears forever.

While religion isn’t explicitly mentioned until after the page that says “the end,” the influence of scripture is obvious (the seed packets are labelled things like “mustard,” “sycamore,” “olive,” “grape,” and “fig,” and it makes references to “mansions” and “vineyards”). The seed is everyman (or everychild), and the farmer is God the Father, and/or authority figures like parents and teachers.

It sounds helpful and wholesome, but let’s take a closer look.

Margaret Realy, author, artist, and speaker (The Catholic Gardener) reviewed the book, anticipating a pleasant read, but was alarmed and disturbed. She wrote a review on Amazon that pinpoints the specifics. Realy said:

This story places childhood abuse and neglect in the center of its theme. A small defenseless being is repeatedly traumatized by seeing loved ones ‘disappeared’ “…and no one would see that seed anymore.” Then the following stanzas speak of anticipatory trauma that he too will be taken away.

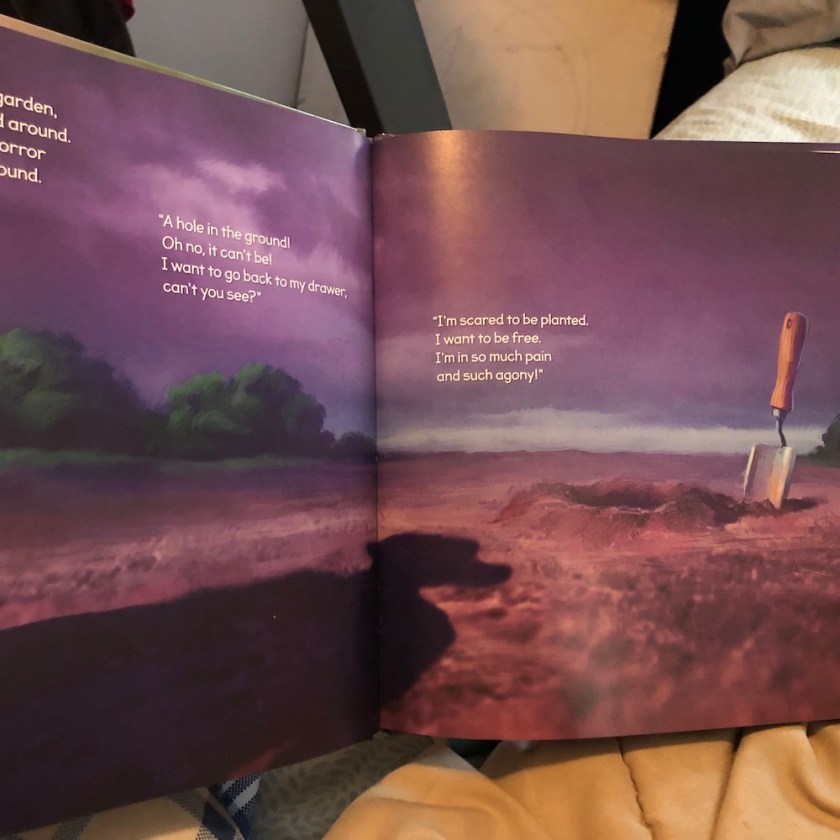

The fearful day comes, he can’t escape, and the man’s hand clasped around him. No matter how the seed cried and yelled, he was taken from a secure and loving environment to one of “horror”, “pain”, and “agony.”

The man that took him away was silent and unresponsive to the pleading seed, buried him alive, and left him abandoned.

That’s a lot for a young child to process, and nearly impossible for one—of any age—that is abused.

The pictures are dramatic and gripping, and the dark subject matter contrasts weirdly with the cartoonish faces and font:

Here is the seed, weeping after being abruptly buried alive:

The seed does, of course, come out well in the end, and it becomes a home for birds and animals; children play around it, and it bears much (confusingly diverse) fruit while overlooking a prosperous paradisal landscape with “millions of mansions.”

But this happy ending doesn’t do the job it imagines it does. Realy points out that, while the story attempts to show that the seed’s fears were unfounded and it would be better if he had trusted the farmer, it doesn’t show any of that in progress. Realy said:

Unfortunately I find the story’s transitioning through fear of the unknown into transformation by Grace, weak. The ‘seed’ began to change without any indication of the Creator’s hand, and his terrified soul was not comforted or encouraged by human or Holy.

Instead, it simply shows him transforming “all at once, in the blink of an eye”

This might have been a good place to point out that a seed grows when it’s nourished by a farmer, and to illustrate what appropriate care and concern actually look like. The Old and New Testament are absolutely loaded with references to God’s tenderness, kindness, mercy, love, care, pity, and even affection; but this book includes none of that, and instead skips seamlessly from terror and abandonment to prosperous new life.

It explicitly portrays God (or his nearest representative in a child’s life) as huge, terrifying, silent, and insensible and unresponsive to terror and agony — and also inexplicably worthy of unquestioning trust.

Realy points out:

Research indicates that up to 25% of children in the United States are abused, and of that 80% of those children are five and under (Childhelp: Child Abuse Statistics Facts. Accessed December 2019). This is based on only reported cases.

That’s a lot of kids.

Imagine a child who has been taken from a place of comfort, happiness, and companionship and is thrust into darkness and isolation by a looming, all-powerful figure who silently ignores their terror and buries them alive.

Now imagine what this book tells that child to think about himself, and what it tells him to think about God. Imagine how useful this book would be to someone who wants to continue to abuse, and who wants his victim to believe that what is happening to him is normal and healthy and will bear fruit.

It is ghastly.

But what about kids who aren’t being abused? The statistics, while horrifying, do show that most children aren’t being abused. Can’t we have books designed for these typical children?

It is true that some kids are inappropriately afraid of change and growth, and need to be reminded that the unknown isn’t always bad. Imagery is useful for kids (and for adults), and I can imagine an anxious child who’s afraid of going to second grade being comforted with a reminder: Remember the little seed? He was scared, too, but the new things turned out to be good and fun!

But even for these children who aren’t experiencing massive trauma or abuse, and who truly are being cared for by people who want good for them, the narrative minimizes and delegitimizes normal childhood emotions. It’s clear that the seed is wrong to be afraid, even though his situation is objectively terrifying. Teaching kids to ignore and minimize their powerful emotions does not facilitate growth or maturity; it encourages emotional maladaptations that bear bad fruit in adult life. Ask me how I know.

The flaws in the book are especially egregious when they make the message explicitly spiritual. The final page says “From the Bible” and quotes four passages from scripture. Two are unobjectionable, but two are breathtakingly inappropriate for kids: One quotes John’s passage about a grain of wheat falling to the ground and dying; and one describes Jesus falling to the ground at Gethsemane and praying that the Father might take the cup away, but saying “Yet not as I will, but as you will.”

These are not verses for children! They are certainly not for children of an age to appreciate the colorful, cartoonish illustrations and simplistic rhyming stanzas in the book. These are verses for adults to grapple with, and goodness knows adults have a hard enough time accepting and living them.

Including them in a book for young kids reminds me chillingly of the approach the notorious Ezzos, who, in Preparation for Parenting, urges parents to ignore the cries of their infants, saying, “Praise God that the Father did not intervene when his Son cried out on the cross.” I also recall (but can’t find) reading how the Ezzos or a similar couple tell parents to stick a draconian feeding schedule for very young babies, comparing a baby’s hungry cries to Jesus on the cross saying, “I thirst.”

On a less urgent note, it’s also sloppy and careless with basic botany. Realy, an avid garner, points out its “backwards horticulture” which has the tree growing “nuts and fruits that hang down,” but then later “the tree sprouted flowers/and blossoms and blooms.” It also shows a single tree producing berries, fruits, nuts, and grapes, refers to how “woodpeckers pecked/at his bark full of sap.” Woodpeckers do not eat sap, and sap is not in the bark of a tree. Realy and I both also abhor the lazy half-rhymes that turn up, pairing “afraid” with “day” and “saw” and “shore.”

But worse than these errors is the final page, which shows a beaming, full-grown tree, along with a textbook minimization of trauma:

“The tree understood

that he had been freed.

He barely remembered

when he was a seed.

He barely remembered

his life in the drawer.

his fears disappeared

and returned . . . nevermore.”

Again, if we’re talking about a kid who was nervous about moving to a new classroom, then yes, the fears might turn out to be easily forgotten. But that’s not what the book describes. When the seed is being carried away from its familiar home, it says, “I’m in so much pain and such agony!” and “He felt so abandoned, forsaken, alone” as he’s buried alive by a giant, faceless man who offers no explanation, comfort, or even warning. In short, it describes true trauma, and trauma doesn’t just “disappear and return nevermore.” It’s cruel to teach kids or even adults to expect the effects of trauma to vanish without a trace.

As Realy said: “PTSD never goes away, even with God. We learn to carry the cross well.”

Let’s be clear: Children don’t need everything to be fluffy and cheery and bright. Some kids, even very young kids, relish dark and gruesome stories, and I’m not arguing for shielding children from anything that might possibly trouble or challenge their imaginations. We recently read Robert Nye’s Beowulf, for instance. We read mythology; we read scripture.

But when we set out to explicitly teach a lesson — especially a lesson that purports to speak on behalf of God! — it’s vital to get the context exactly right. This book is so very sloppy and careless with children’s tender hearts, that even if there isn’t some dark intention behind it, it’s very easy to imagine a predatory abuser using it as a tool.

A Catholic publisher like Sophia Institute Press ought to know better.